In 1900, Frank Baum published The Wizard Of Oz in Chicago…

If you grew up watching MGM’s astonishing movie version of “The Wizard of Oz” when it came along every Easter Sunday, then the statues in Oz Park in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood are a must see!

It’s a monument dedicated to Chicago author Frank Baum who wrote it as a fairy tale, yet, within it were many hidden tales told, particularly the embedded meaning behind the Yellow Brick Road being a symbol of the gold paving the way for America’s financial system.

My two brothers and I lived on North California Avenue, on Chicago’s Northwest side. We didn’t know that Frank Baum’s home in the 1600 block of Humboldt was just a short walk away.

About a century later, a civic minded group decided to commemorate Baum’s work by commissioning metal working artists to replicate the world-known Oz characters and place the statues in a park:

The Tin Man came first in 2001

The Scarecrow sculpture was added in 2005

…Then Dorothy in 2007…

…and a closer look at Toto

Gasp! Is the wicked witch next?

The flower-spangled Emerald Garden is a bonus.

[swtrekker, 07/04/2011]

In another memorial to Baum’s heritage around the same time, Chicago’s nonprofit developer Bickerdike Redevelopment Corporation constructed a reproduction of the Yellow Brick Road at Humboldt Boulevard and Wabansia Avenue, in front of the home where L. Frank Baum wrote “The Wizard Of Oz”.

Political interpretations of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz include treatments of the modern fairy tale (written by L. Frank Baum and first published in 1900) as an allegory or metaphor for the political, economic, and social events of America in the 1890s. Scholars have examined four quite different versions of Oz: the novel of 1900, the Broadway play of 1902, the Hollywood film of 1939, and the numerous follow-up Oz novels written after 1900 by Baum and others.

The political interpretations focus on the first three, and emphasize the close relationship between the visual images and the story line to the political interests of the day. Biographers report that Baum had been a political activist in the 1890s with a special interest in the money question of gold and silver (bimetallism), and the illustrator William Wallace Denslow was a full-time editorial cartoonist for a major daily newspaper. For the 1902 Broadway production Baum inserted explicit references to prominent political characters such as then-president Theodore Roosevelt.

Monetary policy

In a 1964 article, educator and historian Henry Littlefield outlined an allegory in the book of the late-19th-century debate regarding monetary policy. According to this view, for instance, the Yellow Brick Road represents the gold standard, and the Silver Shoes (Ruby slippers in the 1939 film version) represent the Silverite sixteen to one silver ratio (dancing down the road).

Others have suggested that the City of Oz earns its name from the abbreviation of ounces, “Oz”, in which gold and silver are measured.

The thesis achieved considerable popular interest and elaboration by many scholars in history, economics and other fields, but that thesis has been challenged. Certainly the 1902 musical version of Oz, written by Baum, was for an adult audience and had numerous explicit references to contemporary politics, though in these references Baum seems just to have been “playing for laughs”. The 1902 stage adaptation mentioned, by name, President Theodore Roosevelt and other political celebrities.

For example, the Tin Woodman wonders what he would do if he ran out of oil. “You wouldn’t be as badly off as John D. Rockefeller“, the Scarecrow responds, “He’d lose six thousand dollars a minute if that happened.”

Littlefield’s knowledge of the 1890s was thin, and he made numerous errors, but since his article was published, scholars in history, political science, and economics have asserted that the images and characters used by Baum closely resemble political images that were well known in the 1890s. Quentin Taylor, for example, claimed that many of the events and characters of the book resemble the actual political personalities, events and ideas of the 1890s. Dorothy—naïve, young and simple—represents the American people. She is Everyman, led astray and seeking the way back home. Moreover, following the road of gold leads eventually only to the Emerald City, which Taylor sees as symbolic of a fraudulent world built on greenback paper money, a fiat currency that cannot be redeemed in exchange for precious metals.

It is ruled by a scheming politician (the Wizard) who uses publicity devices and tricks to fool the people (and even the Good Witches) into believing he is benevolent, wise, and powerful when really he is a selfish, evil humbug. He sends Dorothy into severe danger hoping she will rid him of his enemy the Wicked Witch of the West. He is powerless and, as he admits to Dorothy, “I’m a very bad Wizard”.

Hugh Rockoff suggested in 1990 that the novel was an allegory about the demonetization of silver in 1873, whereby “the cyclone that carried Dorothy to the Land of Oz represents the economic and political upheaval, the yellow brick road stands for the gold standard, and the silver shoes Dorothy inherits from the Wicked Witch of the East represents the pro-silver movement. When Dorothy is taken to the Emerald Palace before her audience with the Wizard she is led through seven passages and up three flights of stairs, a subtle reference to the Coinage Act of 1873 which started the class conflict in America.”

Ruth Kassinger, in her book Gold: From Greek Myth to Computer Chips, purports that “The Wizard symbolizes bankers who support the gold standard and oppose adding silver to it… Only Dorothy’s silver slippers can take her home to Kansas,” meaning that by Dorothy not realizing that she had the silver slippers the whole time, Dorothy, or “the westerners”, never realized they already had a viable currency of the people.

- The Scarecrow as a representation of American farmers and their troubles in the late 19th century

- The Tin Man representing the American steel industry’s failures to combat increased international competition at the time.

- The Cowardly Lion as a metaphor for the American military’s performance in the Spanish–American War.

Taylor also claimed a sort of iconography for the cyclone: it was used in the 1890s as a metaphor for a political revolution that would transform the drab country into a land of color and unlimited prosperity. It was also used by editorial cartoonists of the 1890s to represent political upheaval.

Dorothy would represent the goodness and innocence of human kind.

Other putative allegorical devices of the book include the Wicked Witch of the West as a figure for the actual American West; if this is true, then the Winged Monkeys could represent another western danger: Native Americans. The King of the Winged Monkeys tells Dorothy, “Once we were a free people, living happily in the great forest, flying from tree to tree, eating nuts and fruit and doing just as we pleased without calling anybody master. … This was many years ago, long before Oz came out of the clouds to rule over this land.”

The previous passages are all from Wikipedia

My brief MGM journey back to Oz

By the mid-1990s, I had 5 feature films in development, from various writers and other producers with fully developed feature films that I represented out of my independent studio, Cinema Equinox in Chicago [Cinequinox Pictures].

I my own prior creative film work, I had met sound engineer Ron Gresham, Aretha Franklin’s favorite sound recordist, who was a master at crafting some of her most memorable songs. Ron was well known at Chicago’s premier sound studio, Streeterville Studios.

Eventually, we worked on a music video produced in Chicago where he did the live sound recordist work on, a production job where I provided him with instructions on using what are called ‘shotgun microphones’ which are in standard use in film production to this day. Later, I learned the basics of studio sound from him.

Eventually, I was invited to move to Hollywood so that greater progress could be made on going into production with the film I had written and was being produced by Warner Brothers.

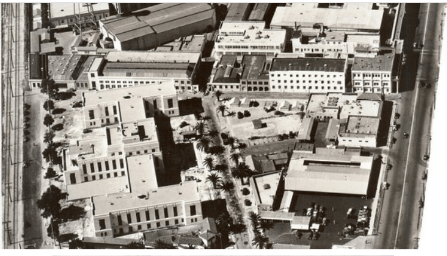

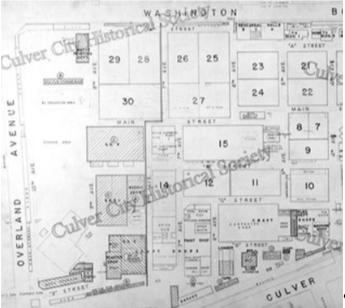

The day after I had arrived in Los Angeles, Ron had arranged for me to visit one of his closest friends who was working as an Assistant Director on a feature film being made at what had been the MGM studios in Culver City. Sony Pictures bought the fabled MGM lot and inherited the famed collection of sound studios from 1924 to 1986, including the largest of them all, Stage 15.

I was lucky to be able to park on Overland Avenue right next to the main gate and was checked in and told that Stage 15 was only a short distance from there and I roamed along the Main Street soundstages in a state of astonishment. Movie history raced through my mind as I walked by buildings featuring the names of MGM contract actors like Clarke Gable, Judy Garland, Rita Hayworth and Burt Lancaster.

I got to the immense building and there was a big red light with a sign next to it that warned people not to open the door when it was lit during filming. Upon cracking it open, it was a foot thick to be fully soundproof. I stepped in and was in awe of the size of the studio: The interior would hold a Goodyear Blimp, my best way to describe the enormous space. It seemed to stretch into the distance for 3 city blocks.

In the distance, I recognized a small set where I knew from my own film work was where the day’s work was being shot. Lights poured out from inside the cubicle constructed, with huge air conditioning tubes feeding into the set. Nearby were the traditional fold-up cloth deck chairs for the actors whose names appeared on them: George Segal and Tuesday Weld.

My Assistant Director friend of Ron Gresham walked up and welcomed me kindly, explaining that he and Ron had grown up together in Chicago. Soon, I had to ask what the title of the film being shot was. “It’s ‘The Cable Guy’ with Jim Carrey . Ben Stiller is directing it.”. I had to laugh, having been a fan of ‘In Living Color’.

I had to remark about using such a large sound stage for a tiny set. “It’s an room in an apartment,” he explained. Then he went on to tell me that Stage 15 was where all of the main sequences of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz were shot. At that moment, the magical sensations of being in Oz took over and many of the scenes from the film swept through my mind. With closed eyes, I could see the Yellow Brick Road right there. I wanted to step onto it myself.

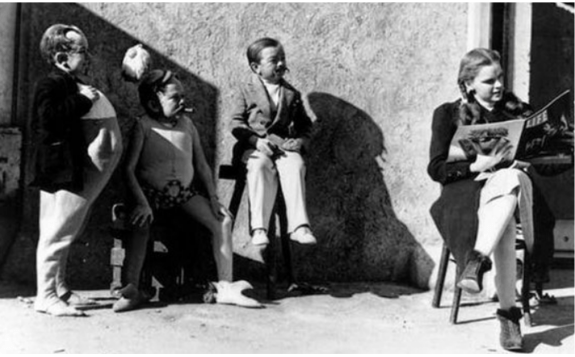

During the production, the little people that played the Munchkins stayed at the Culver Hotel, a short distance away from the studio backlot.

“I’ve gotta go,” he excused himself, “Make yourself something over there at the craft services table and I’ll see you again in a few minutes.”

As my strong visions of Oz began to fade, I turned and began making a cup of coffee when I heard cowboy boots clomping near and laughter. It was Jim Carrey arriving for a cup of coffee, with something funny on his mind. He turned and asked me if I’d pass the sugar. “Sure,” I said and, as I passed it over, I said: “Must be amazing to work here where the land of Oz once was.”

Not a moment later, the assistant director walked back to call for him to do the scene.

Thanks to screenwriter Ken Misomoto for providing the story about Stage 15.

woldrob@yahoo.com

Leave a comment